On a typical morning before work, Rodeline rises before the sun. She prepares food for her family and then gathers her buckets and bags to make her rounds to local farmers and markets before searching for transportation to Port-au-Prince from her home in the hard-to-reach northern part of Haiti. Rodeline is a Madan Sara, one of the thousands of women traders who, for more than two centuries, have provided a lifeline to rural farmers by transporting agricultural produce between far-reaching markets, the capital and other cities[1].

These women, with little education and few opportunities, often inherit their profession from their mothers, forming an intergenerational chain of support to a fragile system of trade where it would otherwise cease to exist. Rodeline and her fellow Madan Saras travel by foot, donkey cart, ¡°mototaxis¡± or vans - depending on the load - from a hard-to-reach village in the north of the country to the markets of Port-au-Prince. Once there, they sell the fresh produce purchased from farmers and some household goods and clothes.

Despite their critical importance to the Haitian economy and community, most Madan Saras work in the informal sector without labor market protections and face difficult and dangerous working conditions. Rodeline is among 80 percent of the workers who make up Haiti's informal labor market[2]. Without basic workplace safety or a supervisory structure, Rodeline is exposed to several risks both on her way to work and in public markets. While displaying their goods in the market, Madan Saras frequently report threats of kidnapping and physical and sexual violence perpetrated by males, including youth, gangs, fellow passengers in transport, and marketgoers.

Rodeline also fears for her safety and her livelihood on the way to market. She faces dangerous roadways and poor road conditions with many accidents, potential theft of her goods and cash, and extortion. Further, due to frequent and prolonged travel, Rodeline must decide between caring for her children and working while her family's livelihood is in constant precarity.

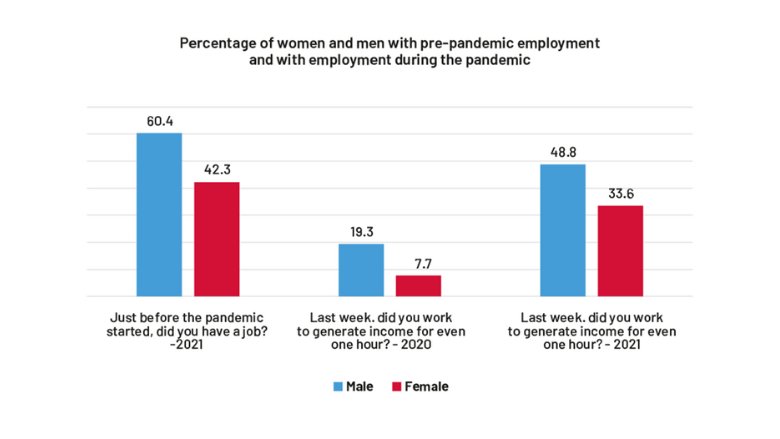

When the first wave of infections from the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in May 2020, Rodeline stopped working as a Madan Sara. She was not the only woman to lose her livelihood; at the onset of the pandemic, only 8 percent of women reported working the previous week, compared to 19 percent of men (figure 1). During the pandemic, women were much more likely to leave the workforce than men, reflecting a pattern of low labor market attachment that was present before the pandemic ¨Cin 2019, women's labor force participation was 62 percent, compared to 70 percent for men¨C and expanded during it. In Rodeline's case, her disengagement from the labor market was due to an increase in household and family duties during this period and expectations placed on her by society to ensure that those household and family duties were attended to.

Figure 1. Employment Status Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Recently, that financial precarity drove Rodeline to consider re-entering the labor market in Haiti by looking for a steady job, with fewer risks. Her hopes clashed with reality. Women's ability to participate fully in the labor market is limited by cultural and social norms and gendered expectations of women¡¯s role in society. As reported in the Haiti Gender Assessment, in May-June 2020, just over half of households in Haiti reported that women were responsible for cooking, washing, and childcare, among other household responsibilities. When women are able to obtain jobs, segregation the workplace limits their opportunities for high pay and advancement. Women most commonly work in service, retail, textile, and trade jobs and infrequently in managerial positions.

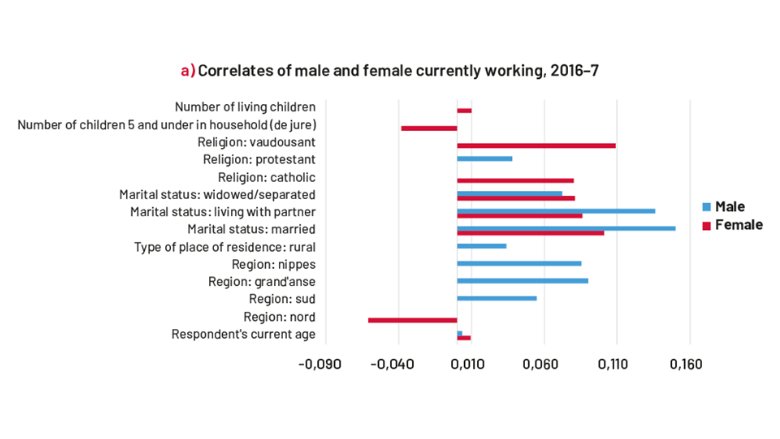

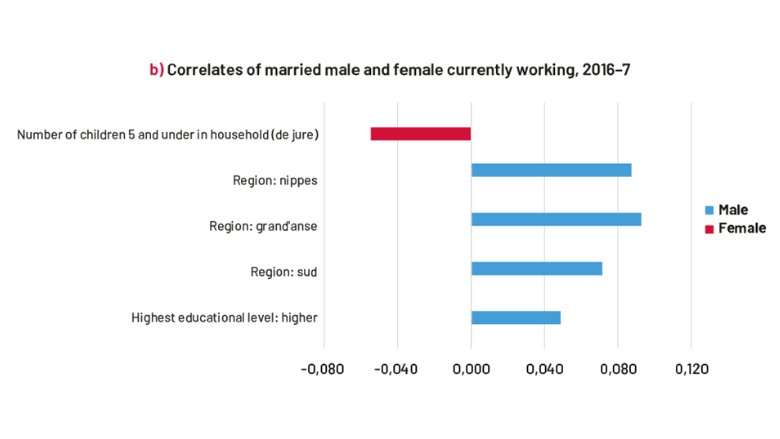

Overall, men are more likely to be employed, more likely to be employed consistently, and have higher rates of labor market attachment. Women like Rodeline are less likely to be active in the workforce. With two children under the age of 5 to care for, it is difficult to work without the children in the household affecting her partner¡¯s ability to work and norms dictating that she should take on those home-based responsibilities (figure 2). Even if she could find a job, female workers report that sexual harassment is common in Haitian workplaces, making work unpleasant, if not dangerous, and further limiting her opportunities for pay and advancement.

Figure 2. Correlates of Engagement in the Labor Market by Gender¡ªMarginal Effects

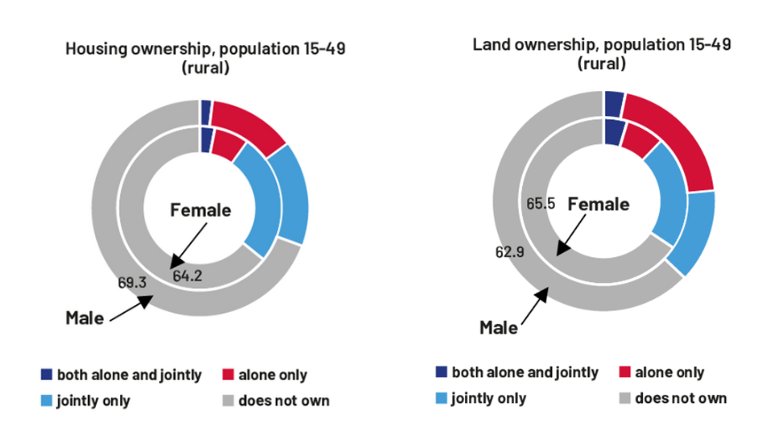

Rodeline might consider starting a business of her own, but her lack of access to physical and financial resources holds her back. In Haiti, especially in rural areas, women like Rodeline are less likely than men to claim sole ownership of productive assets, especially housing and land (figure 3). The lack of access to these assets is an additional obstacle to Rodeline's autonomy and ability to start businesses, take out loans, and engage in farming or other income-generating activities. In addition, like the vast majority of Haitians, Rodeline does not have formal savings or credit opportunities due to the very low density of banks and difficulty opening a bank account. Rodeline's difficulty in accessing productive resources reduces her ability to provide for herself and her family.

Figure 3. Ownership of Property by Gender, 2017

When conditions are right, the implementation of policies to address these constraints could increase opportunities for Rodeline and women like her to close the gender gaps in labor market access. In 2021, there were nearly two and a half million women in Haiti's labor force[1], who, along with Rodeline, are struggling with labor market entry decisions and difficult labor market conditions. However, the latest Gender Assessment for Haiti: Haiti's Untapped Potential: An Assessment of the Barriers to Gender Equality provides this diagnostics, and policy recommendations that made these problems more visible to policymakers and stakeholders. She is hopeful that these conditions could change for women in her community through the implementation of job training programs that have helped women access skills and jobs in other countries and communities. These programs could consider specific trades or sectors in which women are traditionally underrepresented, and provide childcare, food, and transportation subsidies.

These programs typically also cover topics such as self-esteem, civic engagement and leadership, reproductive health, gender-based violence, preparation for the workplace, financial literacy, business skills, digital literacy campaigns and programs to create job opportunities and improve business environment that could help women and girls in Rodeline's community remedy informational, social, and financial capital gaps alongside with preventing and responding to gender-based violence.

[1] According to Hossein (2015). Retrieved from:

[2] According to UNDP (2015). Retrieved from:

[3] According to ILO modelled estimates for 2021:

Story by Gustavo Canavire-Bacarreza, Erin Fletcher and Marlen Cardona