There is an old Arabic proverb that goes ˇ°Qalb al-um madrasat al ?iflˇ± (??? ???? ????? ?????) which translates to ˇ®a motherˇŻs heart is the childˇŻs schoolˇŻ ¨C a common expression that illustrates societal expectations related to the role mothers play in caring for their children and influencing their human development outcomes.

In the Middle East and North Africa region, like in many parts of the world, women are expected to be primary caretakers in the home. Some of this is due to social norms but there are other important reasons, such as limited access to affordable childcare of quality.

This lack of childcare comes at a cost: the ILO estimates that globally, in 2018, 647 million working-age adults were hindered from entering the workforce due to family responsibilitiesˇŞ94% of whom were women. In the MENA region, the lack of childcare options is identified as the most challenging barrier for women to join the labor market (Arab Barometer 2021-22).

The link between access to childcare services and female labor force participation is striking. A 2023 study published by the Mashreq Gender Facility (MGF), entitled , shows that expanding options for quality and affordable childcare services could increase female labor force participation (FLFP) by 2.5 percentage points in Jordan, 2.1 in Lebanon and 0.5 in Iraq. If childcare was free, expected changes in FLFP can be as much as 7.3 and 7.1 percentage points in Jordan and Lebanon, respectively.

Female labor force participation in the Mashreq countries is among the lowest in the world --- with less than 15% of women either employed or actively seeking work in Iraq and Jordan and only 26% in Lebanon. Care responsibilities directly impact womenˇŻs opportunities to work.

Every day, and three times more than fathers on domestic chores. For mothers who are employed, a typical ˇ°workdayˇ± is 12 to 14 hours long, taking into consideration both paid and unpaid work. For each additional hour spent on care activities, the probability of being in the labor force drops by up to 3 percentage points.

Yet womenˇŻs contribution through unpaid care work is not adequately recognized. Based on the study, the time that Mashreq mothers spend in unpaid care work would account for as much as 6% of the regionˇŻs GDP (if valued at minimum wage). Lack of recognition underestimates both womenˇŻs contribution to the economy and the important need for addressing childcare as an economic imperative.

The childcare landscape in the Mashreq is characterized by high cost, poor quality, and low demand. Many factors, from affordability and quality of available childcare facilities to prevailing social norms, influence demand for services which can then ultimately affect supply.

With limited free public childcare service provision and targeted childcare subsidies to households, access to quality childcare services is unaffordable for most. Not surprisingly, utilization is low and households resort instead to informal arrangements, such as family or relatives, many times on an ad-hoc basis.

In Jordan, only 2.3% of children aged 0 to 5 years old are benefiting from formal childcare services. In Iraq, the corresponding share is 0.7% for children aged 0 to 4 years and in Lebanon it is 4.8% for children 0 to 3 years old. In all three countries, well over half of mothers rely on family, friends, and neighbors as the main source of care support for children aged five and under. Global trends point to similar statistics: a survey across 31 developing countries showed that .

On average, around one in four mothers of children below primary school age not currently using any sort of childcare (formal or informal) would be willing to use formal services. However, demand is highly sensitive to cost and in it is the key consideration for utilization given the multiple crises.

Figure 1: Willingness to use formal childcare services among mothers with children [0-5] not currently using them

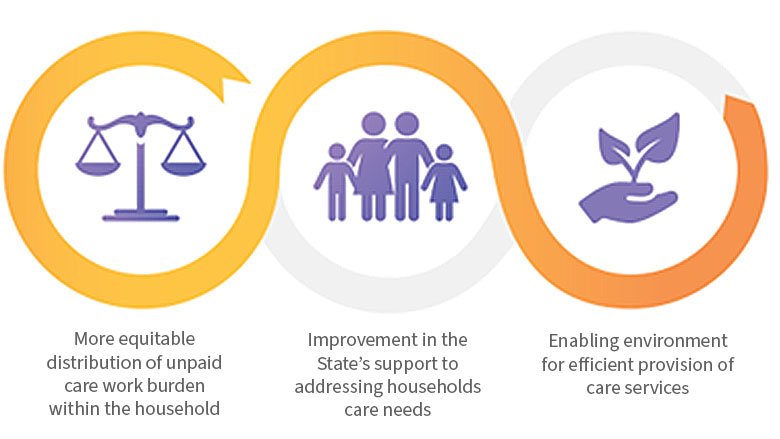

Solutions that combine raising awareness, streamlining reforms, and creating incentives are needed. Our report advocates three overarching recommendations to support the provision of childcare in the Mashreq:

Figure 2: Three Overarching Policy Recommendations

- Distribute the unpaid care work burden more equitably. Raising awareness of the economic value of womenˇŻs contribution to the household and society welfare is a first step. Mashreq countries could collect regular data on time-use as an integral part of national household surveysˇŻ systems, and compile Household Satellite Accounts measuring the productive (but non-market) role of the household alongside the market economy.

- Improve the stateˇŻs support to address household care needs. This would entail enhancing availability of affordable small-scale childcare options which help the most vulnerable. Jordan has recently taken many steps to increase female labor force participation [and] among these reforms is regulation to ease licensing procedures for nurseries. Iraq and Lebanon should embark on licensing of homebased childcare centers which could help parents facing .

- Provide an enabling environment for the efficient provision of quality childcare services. Improving the design and expanding financing of existing care policies could be considered through general taxation or employer social security contribution. This is currently done in Jordan where employers contribute a minimal share of both men and womenˇŻs salaries towards a dedicated social security fund. Countries could also consider providing monetary incentives to promote contribution by employers, such as matching contributions or providing tax credits. For this to take place, better coordination across line ministries and different stakeholders is needed across the board with more emphasis on establishing professional standards and providing career long professional development in all three countries.

![Figure 1: Willingness to use formal childcare services among mothers with children [0-5] not currently using them](https://worldbank.scene7.com/is/image/worldbankprod/MGF-figure-1?wid=780&hei=439&qlt=85,0&resMode=sharp)